The summer break might have tamed the student protests in Quebec, but Premier Jean Charest’s early election call has ensured his proposed tuition hikes will stay on the political agenda.

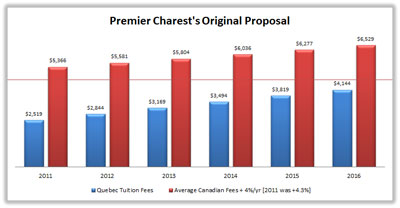

The protests started back in 2011, when the Charest government proposed to modestly increase tuition fees over the next five years. Quebec’s tuition fees haven’t increased for 33 out of the last 43 years and this has made the entire system financially unsustainable.

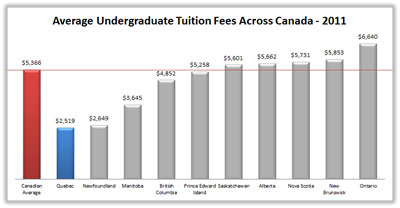

Figures from Statistics Canada show that, for the 2011/2012 year, undergraduate students in Quebec paid an average of just $2,519 a year for their education. Meanwhile, students in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Ontario paid $5,601, $5,662 and $6,640 a year, while the Canadian average was $5,366 a year.

Charest’s tuition proposal would have seen Quebec students still paying thousands of dollars less for their tuition in 2017 than students in several other provinces are paying right now.

No organisation, universities included, can continue to provide a quality service if its expenses go up while it is unable to raise sufficient revenue to cover those expenses. In fact, many university officials had actually hoped for larger increases in fees to help them address the chronic underfunding their institutions face compared to their counterparts in other provinces.

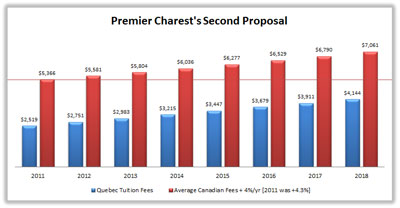

Yet Charest was forced to water down his proposal, spreading the proposed tuition increase out over an extended seven-year period instead of five. The new proposal barely covered the cost of inflation over the 2012 to 2019 period, but was still rejected by student groups as unfair.

“Money shouldn’t be an issue,” one student leader said when asked how else tuition could be funded.

Don’t expect the election to end the dispute though. Just last week another student union spokesperson said, “If another political party is elected, for example the Parti Québécois, there will have to be negotiations. The party will have to respond to our demands.” It’s this kind of attitude that shows that the student unions will keep fighting against even modest and reasonable tuition increases, regardless of the result of the election.

The problem is that Quebec’s student unions have not set any goal to achieve. Theirs is a moving target that no government, of any stripe, will be able to hit. It’s something I’ve seen before.

In New Zealand, where I attended university, there is very generous support for those undertaking higher education. As just one example, many students are given a “Student Allowance” of hundreds of dollars a week in cash that can be spent on anything. This money never has to be paid back and often ends up going towards beer.

But even with such generous arrangements, student unions in New Zealand weren’t happy so they organized campaigns and successfully pushed the Labour government of the time to introduce caps on tuition fee increases. Next, the student unions called for all student loans to be completely interest free — a policy the government then campaigned for re-election on and proceeded to implement. Still not content, the unions have now moved on to campaigning for no tuition fees at all, and believe that all previous loans should be completely forgiven. The New Zealand experience shows that when one set of demands is met student unions usually produce a new set right away, often without regard to the cost to taxpayers.

It’s easy to think that provincial matters don’t affect the rest of the country but all Canadians should keep a close eye on the Quebec election. There’s no such thing as a free lunch — someone always has to pay the bill. In this case, thanks to equalisation transfers, taxpayers all across Canada will be forced to pick up part of the tab.

The shortfall in tuition fees that the Quebec government faces is coming straight out of the wallets of students and workers in other provinces where leaders have already made the tough decision to (or, have students pay their own way and to) have higher fees.

Quebec’s student unions should take a hard look at their position. The majority of students just want to study, and the majority of taxpayers just want quality services at a reasonable price. In a real strike, workers risk their incomes and jobs while all that the student protesters have done is put their fellow students’ education at risk.

On average, individuals who hold a university degree earn hundreds of thousands of dollars more during their working life than those who don’t. It is only fair and reasonable to expect them to contribute towards the cost of that brighter future.